What are the NDCs and why are they so important to halting climate change

This has become one of the key tools for measuring what each country is doing in the climate change area.

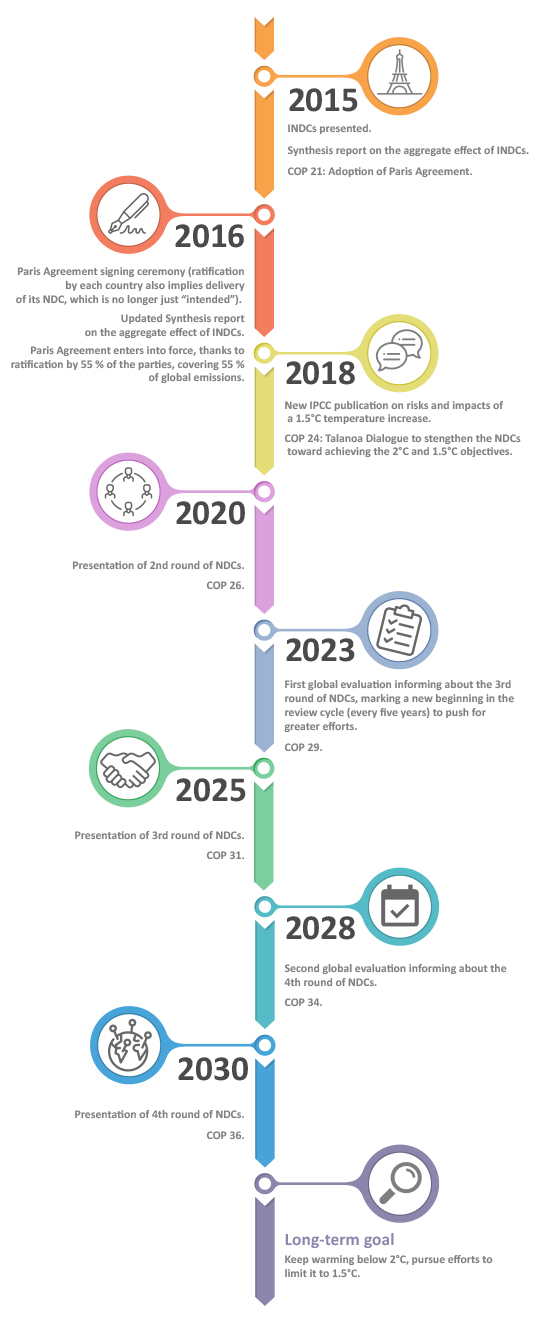

Adoption of the Paris Agreement at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP 21) in 2015 represented one of the biggest climate change milestones in history. A total of 196 Parties (195 countries plus the European Union) made a pact to take drastic measures in the short, medium and long term to fight against climate change.

At the heart of this accord were the INDCs (Intended Nationally Determined Contributions), the fundamental mechanism by which each country would bring to the table the national efforts it planned to take as of 2020 to fulfil the most ambitious objectives in the Agreement: keep the increase in global temperature to well below 2°C with respect to the pre-industrial era, with the further aim of limiting it to 1.5°C; and strengthen the capacity of adaptation to the adverse effects of climate change and increase resilience.

But why are the INDCs so important and how have they evolved since the Agreement?

From the INDCs to the NDCs, national commitments to a global objective

FEATURES OF THE NDCs

UNIVERSAL

Each country must prepare, communicate and record its contributions.

NATIONAL

Each country is autonomous in determining what its contribution will be and how it will be implemented nationally.

INTEGRATED

Countries must deliver a minimum of information to be able to determine the sum of the efforts.

MINIMUM REQUIRED

Once it has presented them, no country should reduce the scope of its objectives.

PUBLIC

The NDCs must be open to public scrutiny.

The acronym, INDC, emerged at COP 19 in Warsaw. Countries were urged to determine independently what contribution they could make to the global effort to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The initiative was so welcome that, just before the Paris Conference began, over 180 nations representing more than 90% of global emissions had presented their contributions, detailing GHG reduction goals, actions plans (for mitigation and adaptation), as well as financing measures.

All these INDCs were analyzed together in the Synthesis report on the aggregate effect of INDCs. But the report revealed that the sum of the contributions of all the nations did not reach the objective of keeping the planet well below a 2°C increase in global warming.

In fact, the countries had expressed their concern in the Paris Agreement itself, recognizing it would require a much greater effort to reduce emissions than the nationally determined contributions planned so far.

As each country was ratifying the Paris Agreement, the INDC lost its tag of “proposed” and began to be referred as the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). This has since become one of the key tools for measuring what each country is doing in the climate change area. Nevertheless, the Paris Agreement kept an ace up its sleeve: national contributions that do not to achieve the objective toward limiting global warming below 2°C (or with effort, 1.5°C) are to be reviewed every five years, when each country must present a new document with more ambitious plans and objectives in the fight against climate change.

2018 has been full of meetings and considerations that will determine how the proposed new NDS will be drawn up for 2020.

On the one hand, the Talanoa Dialogue (originally known as the Facilitative Dialogue) takes stock of the collective effort the countries are called upon to make and aims to respond to three main questions on climate change action: “Where are we now?”, “Where do we want get to?”, and “How can we achieve it?”. This practice has been undertaken nationally and locally throughout this year.

But, on the other, latest data is far from encouraging. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) fulfilled the role the Paris Agreement gave it by presenting a report explaining the risks and impacts of a 1.5°C temperature increase. This report warns of the consequences of this increase, compared to 2°C, and leaves no room for doubt that the NDCs at the Katowice Climate Summit (COP 24) will have to be more ambitious.

Too little to achieve the goal

Until now, all the independent and institutional reports on the NDCs and the impact of climate change policy measures countries are taking do not augur well. The conclusion is that if the countries do not put their collective foot down, the goal will not be reached.

To date, two official United Nations reports analyzing the sum of the efforts of the NDCs show it is insufficient to limit global warming to 2°C. And, compared with data from other independent organizations, it is certain this is a somewhat conservative analysis. Another study, the Climate Action Tracker, claims that, if current emission trends continue, it is 50% probable the temperature will have risen by 3.16°C or more by 2100. And, on the basis of the first NDCs, there is still a more than 90% probability the temperature will go over 2°C, even if the national plans are fully implemented. In the following interactive map, Climate Action Tracker highlights the state of each country in color and their NDCs.

It is a worrying outlook. Countries such as Switzerland, for example, which proposes reducing emissions by 50%, and Norway and the European Union, which plan to reduce theirs by 40%, still have to come up with even more ambitious plans if the global objective is to be reached. Nations like the US and Russia, two of the most polluting countries according to emissions data, propose timid reductions of 26% and 28%, which sees them belong to the pack of countries facing the greatest environmental challenges in future.

One of the most delicate points in the negotiations between governments is the developed country financing of developing countries, an issue that directly affects the NDCs of many nations. Mexico and Chile, for example, could raise their emissions reduction targets by 25-40% if they were to receive international support toward reaching them.

The environmental challenge we have before us Is alarming. Although it is still possible, based on today’s emissions levels, to overcome the challenges set by the Paris Agreement, with every decade that we fall behind, the difficulties increase and at some point in the future, if we do not implement what the countries have promised, the problem could become irreversible and impossible to rein in.

Sources: UNFCCC, Climate Accion Tracker, CDKN, IPCC, CEPAL, Ministerio de Ambiente de Perú, EFE